By the late 90s, streaming video had started to become the norm. Unlike in previous years, where the video had to be downloaded in its entirety before viewing, streaming is characterised by playing the video data as it's received.

First, this requires a special compressed video format to facilitate play while downloading. The viewer has to buffer enough data to play should there be some network contention; a few seconds' worth, say. The protocol between viewer and remote media server must allow for renegotiating the resolution of the media should the latency or bandwidth of the network change. If the network latency increases and/or the bandwidth decreases, a lower resolution may be more acceptable than introducing stuttering to the user's playback experience.

Before the turn of the millennium, there were several competing streaming video viewers available. The first was Real Player, which was launched in 1997 and had been demonstrated from 1995. Microsoft implemented streaming video playback in Windows Media Player in 1999, as did Apple with QuickTime.

These streaming viewers required websites to install the corresponding media servers in order to provide properly formatted streaming video for playback, and so, for a few years, users had to contend with the possibility of needing to install three incompatible viewers in order to view content.

This state of affairs continued until about 1992 when Macromedia Flash became prevalent. In essence, alongside animation, programmability, games and so on, it provided a multi-platform, multi-browser streaming viewer, free of charge, and free of the vendor lock-in that characterised its predecessors.

Flash became so successful that it was available on the vast majority of PCs, and formed the basis of streaming sites, such as YouTube, Vimeo and so on (Netflix uses Microsoft's Silverlight streaming viewer). Nowadays, there has been a move away from Flash as a streaming viewer; it requires some fairly intensive CPU resources and therefore compromises the battery life of mobile devices such as smartphones and tablets

Pseudo-streaming

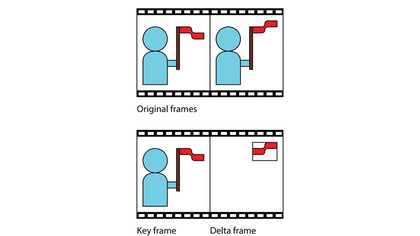

FIGURE 2: Inter-frame compression showing keyframe and delta frame

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Nowadays, video streaming tends to split into two camps: there's what might be called pseudo-streaming and there's streaming proper.

Pseudo-streaming is characterised by downloading an actual file and playing that file as it's being downloaded. YouTube videos tend to be of this variety; you download a video file (and save it temporarily), and play it back during the download. Since the complete file is downloaded, replaying a YouTube video tends to be very quick: there's no more data to download. The file is, however, managed by the viewer and will be deleted once the user moves away to another video.

The media server is different for pseudo-streaming as well. In essence, it operates as a big peer to peer file server: it stores a set of files and will send one as fast as possible to a client requesting it.

Nevertheless, pseudo-streaming allows for seeking to a particular point in the video, without having to download all the video data in between. Pseudo-streaming also uses plain HTTP as a delivery protocol, meaning that it is available on local corporate networks that may block other ports.

Real streaming, on the other hand, is characterised by a data-buffering viewer (all data is kept in memory), with no file being saved on disk. Real streaming also allows for automatic resolution changes (say from 720p to 480p or vice versa) to contend with real-time changes to the network throughput or latency, whereas pseudo-streaming has no such feature. Of course, with some YouTube videos you can elect to view the video in a higher or lower resolution, in which case the video resumes at the changed resolution.

For this to work though, the video must have been uploaded at those different resolutions in the first place. The server, in effect, has to store multiple resolution versions of the video.

Media servers that provide real streaming use a different protocol and port to provide video and audio streams. A common protocol used is RTMP (Real-Time Message Protocol, an Adobe standard used by Flash streaming), where the port used is 1935 (HTTP's is 80). There are other variants, including one that tunnels streams through HTTP.

There are also other protocols in use such as RTSP (Real-Time Streaming Protocol), which uses RTP (Real-time Transport Protocol) and RTCP (Real-Time Control Protocol). These protocols break up the streams (generally there are more than one, such as a video and an audio channel) into very small packets and then transmits them to the client viewer.

All in all, streaming video has come a long way. Nowadays it's a big part of modern online society, from cat videos all the way to live HD broadcasts of the Olympics. In the audio space it's all Spotify and Pandora, the new individualised internet radio stations. In the future? All that and more.