How 3D TV works

On the small screen

Although this system promises a great deal, it's extraordinarily difficult to convert for use with TVs in the home. Since there's no projector (which can easily be modified to produce polarised light), you would have to coat the screen with some kind of polarising film first, which would cut down the light output.

So what can we do instead? Cut to a couple of years ago, when plasma and LCD screens finally became fast enough to work with a new method of creating a 3D effect. With this new method, you're still going to be wearing a special type of 3D glasses to watch something on the screen, but this time the glasses are active - not passive like in the anaglyph and polarised systems.

What this means is that the glasses work in concert with the TV in order to control what each eye sees. The lenses in the glasses use LCDs (liquid crystal displays) to block and then allow light though to the eye. The glasses alternate quickly between the left lens being opaque (right lens clear) and the right lens being opaque (left lens clear), back and forth.

The glasses communicate with the TV using infrared, so that this on/off cycle is synchronised with the TV image. The TV alternates between a left-eye frame and a right-eye frame very quickly at the same rate as the glasses are shuttering opaque/clear.

This TV/glasses synchronisation means that your left eye only sees the left-side frames and your right eye the right-side frames. If you weren't wearing the glasses, you'd see a slightly blurry video.

Just like with movies on film, this image switching and TV/glasses handshaking happens quickly enough that each eye sees continuous motion and the view just for that particular eye.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

For many years, plasma and LCD screens couldn't refresh fast enough for this trick. It's only recently, with the advent of 3D-ready TVs and monitors, that screens have become able to refresh quickly enough for the process to work effectively. In essence, the panel TV must refresh at 120Hz - double the refresh rate of a standard LCD panel.

This means that in order to watch a 3D movie on a TV, you must have a 3D-ready TV, an IR transmitter (although some now use radio or Bluetooth instead) and a pair of shutter glasses (as they're called).

Although there's movement towards standardisation of the synchronisation chain, it's still advisable to buy all the parts from the same manufacturer.

Glasses-free HD

Despite the impressive progress made with passive and active glasses, there's still the nirvana of watching 3D without the need for any glasses at all.

The best solution so far is lenticular displays. These displays have myriad tiny lenses (called lenticules) on a corrugated film on the screen. The screen uses these to display two images simultaneously in such a way that the lenticules aim the left frame in a different direction from the right frame.

If your head is in the so-called sweet spot, your left eye will only be able to see the left frame and your right eye the right frame. Unfortunately, there are numerous problems with this system that make it difficult to implement.

First of all, the left and right frames must be interlaced into a single image in such a way that the lenticules direct the light in the correct course. The screen must have the lenticular film correctly and precisely aligned. The viewing angle is somewhat small - you must be perpendicular to the screen and the sweet spot is fairly small (at least when compared to a 3D-ready TV, for example).

Nevertheless, lenticular displays are looking promising, although there's quite a long way to go before they're a practical alternative.

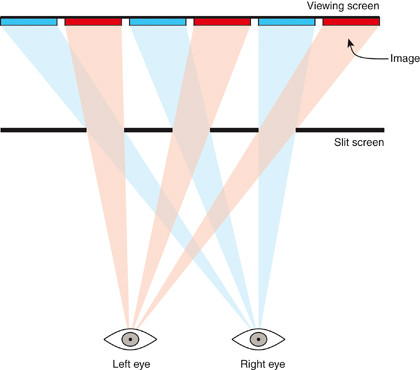

A more popular auto-stereoscopic system is called parallax barrier. This is the system that's used on the new Nintendo 3DS gaming console. The effect is produced by two screens, one on top of the other (the 3D screen is produced by Sharp).

The top LCD screen produces a set of very fine slits, each a pixel wide, through which the bottom screen can be viewed. Since the device is close enough to your face, your eyes will see different views of the display on the second bottom screen. This is all that's needed for the brain to convert the two different images into a single 3D rendition.

Figure 3 shows a stylised example with three slits, where the left frame is coloured red and the right frame cyan.

The parallax barrier suffers from the same problem the lenticular screen does, in that there's only a small zone that produces the 3D effect, but for a small device like the Nintendo 3DS, that sweet spot is where you'd normally view the screen anyway - about two feet away.

Again, just as with the lenticular screen, the left and right frames have to be precisely interlaced so that the 3D effect is produced.

For games, this is relatively simple: instead of producing a single frame for the game's 'video', you have to produce two, each from a slightly different viewpoint (requiring twice the processing). 3D movies have to be converted from their default form to an interlaced form.

So there you have it. We've gone from the very earliest to the most up-to-date methods of showing 3D content. Given the state of flux, when are you going to put your money?

Personally I think the Nintendo 3DS shows the way, but it'll be a while before large screens will be able to do the same.