The many faces of in-game advertising

How in-game ads can help pay for titles big and small

The eighties were riddled with adver-games, and that trickled out into the nineties too. Pepsi Invaders was quickly followed by similarly heavy handed promotional video games that featured the likes of Johnson & Johnson's Tooth Protector and Kool-Aid's human pitcher of juice, the Kool-Aid Man.

That was followed by 7 Up's Cool Spot on the Mega Drive and Cheetos' Chester Cheetah: Too Cool to Fool on SNES.

Volvo: Need for Tweed

Today few modern brands bother to continue the traditions of adver-games because of the difficulty of finding an accepting market. The classically-styled adver-game has been crossed off the list of relevant genres and relegated to the ranks of interactive banner ads and free CD giveaways wedged in your mailbox.

It's only natural that modern adver-games in the vein of Pepsi Invaders are rarer finds on PCs and consoles as society, as a whole, has become more adept at blocking the messages they attempt to peddle.

There are always exceptions, and in 2003 Volvo made a go of it with their Xbox release Drive for Life. Burnout: Paradise It Ain't. Drive for Life was a pseudo-simulator designed for the sole purpose of marinating users in the brand's core value: car safety. The game challenged you with such tasks as moose-avoidance and the mouthwatering objective 'avoid pile-ups'.

Beyond the problems of developing a game that can actually compete in a market that expects the cutting edge, the real difficulty is finding gamers who have been clamouring for a good 4-door hatchback racer. Anyone?

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Deodorant for the covert op in you

These days modern games embrace a level of subtlety that wasn't required twenty or thirty years ago. We're a street-smart bunch, we sniff out the heavy-handed promotional rubbish they throw at us, and both developers and ad agencies alike have learned to cater to this.

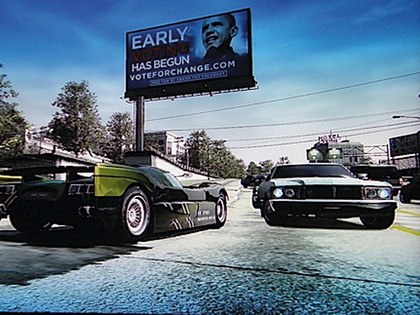

The next logical alternatives came in the form of static and dynamic in-game ads. Both kinds of adverts could be incorporated into a game's environment and placed in a natural setting. It was a slightly more subtle approach to promoting brands, and in some instances they actually helped to create an authentic-looking setting for the game.

An early example of this kind of advertising can be found in 1992's FIFA International Soccer, a game that featured a football field decorated with Adidas banners.

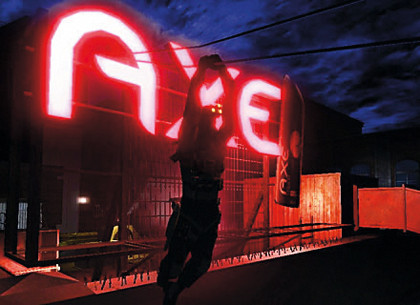

Similarly, 2005's Splinter Cell: Chaos Theory slid in an enormous, glowing neon AXE billboard into the New York mission. Players, controlling Sam Fisher, had to zap the AXE sign with their EMP pistol to get to a strategically placed zipline undetected, which led on to an adjacent building.

Both of these were static in-game advertisements insofar as they were put into the game and could not be changed on the fly. But dynamic ads let developers and ad agencies create advertisements that could be modified at any time, allowing campaigns to be promoted depending on their relevance at the time.

If a film needed promoting for a November release date then it could be done, and it could be pulled a month later when its promotion was no longer necessary.

In-game ad networks, such as Massive, IGA and Extent made dealing with in-game ads almost as apple-pie simple as churning out a web banner for your website by including a string of code in the upcoming title that let networks stream ads from their servers when the game was released.

The upside to this for the networks and game developers has been that they have avoided hard-coding an advert into a game for a single product that might not be relevant in six months' time and, in theory, offer a supply of relevant and up to date ads.